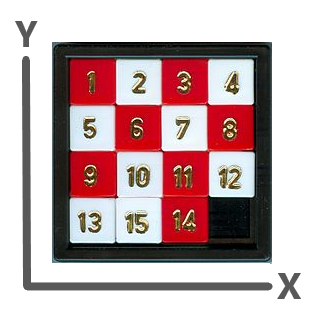

You’ve probably played with a ‘15 puzzle’ or ‘8 puzzle’ sliding puzzle before, and likely even solved it. I’ve owned many cheap plastic 8 puzzles over the years, since they were a staple of birthday party goodie-bags. An 8-year-old can figure out the 8 puzzle within a couple of minutes. If you’re not familiar, sliding puzzles involve sliding numbered tiles around a board until the numbers are in order (top to bottom, left to right), with the blank space in the bottom-right corner.

The ‘15 Puzzle’, invented in 1874.

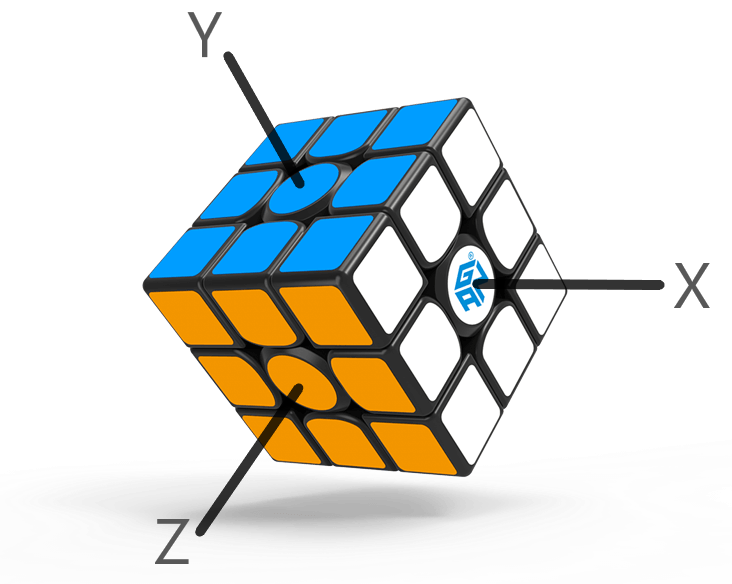

Sliding puzzles are a form of 2-dimensional combination puzzle. They are 2-dimensional because we slide tiles along two axes (horizontal, or x; vertical, or y), and they are combination puzzles because the objective is to reorder the tiles into a particular combination from a random state. The rules of the game are simple. We move tiles along x and y, swapping pieces until the puzzle is solved. Each tile has one (and only one) position it must occupy to be considered solved. We can’t pop tiles out of the board and replace them somewhere else. Of course, the axes are static and don’t mysteriously rearrange themselves.

The two axes of the 15 puzzle, x and y.

It’s impossible to move a piece around the board without affecting other pieces, since there’s only one open space to swap tiles into. As long as our randomized scramble is done from a solved state, the puzzle will always be solvable. If we scramble by popping out the pieces and reinserting them randomly, only half of all possible scrambles will be solvable; our last two pieces can’t be flipped without affecting other pieces.

The above photo of the 15 Puzzle is actually unsolvable - there’s no combination of moves that can solve it, unless we pop out some of the tiles. This only happens if the puzzle is assembled incorrectly by removing and reinserting tiles.

If we know and follow the rules of our sliding puzzle, any scramble that follows those rules is solvable without very much difficulty.

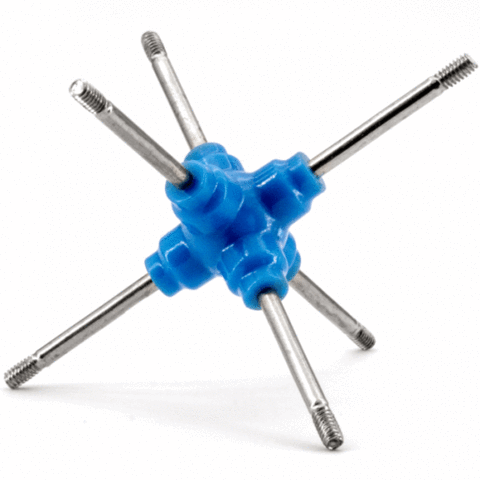

Pieces on the Rubik’s cube move by rotating along three axes: x, y, and z. Like the tiles in a sliding puzzle, the pieces of a Rubik’s cube are not firmly attached to the axes. They lock into one another, allowing the pieces to move freely between layers. The structural integrity of the puzzle requires that all the pieces be hooked into one another; if one piece is pried out, the whole puzzle can collapse.

The Rubik’s cube (or generically, the ‘magic cube’) is essentially the same puzzle in 3 dimensions. In the public imagination the cube is complicated and surrounded by mystery, but it is actually very simple when we consider the rules it follows. It has three axes (x, y, z) which the layers of the cube rotate around. The centre pieces of each color are bound to their axis, and never move in relation to one another; yellow is always opposite white, blue opposite green, and red opposite orange. If we place white on top and green in front, the left centre piece will always be orange, and the right centre piece will always be red. Consequently, there is only one position that each piece can occupy to be considered solved: the white-orange-green corner piece has to occupy the corner between the white, orange, and green centres, and the yellow-blue edge piece has to occupy the edge between the yellow and blue centres, and so on.

The core of a cube (I believe this is from a GAN cube). The centre pieces have been removed, but this firmly demonstrates that the centres cannot move. They only rotate on their axis!

Like the numbers on a sliding puzzle, the colors only help denote the position each piece is supposed to occupy. They’re a rainbow coordinate system. As such, it’s helpful to think of the puzzle in terms of solving pieces or layers of pieces, rather than solving faces. I’ve often seen someone ‘solve’ a single face only to find the pieces were arranged in the wrong order! Each piece gives us two or three bits of information about where it belongs, and we need to utilize all of this information to arrive at a solution. The rule here is: the base unit is the piece, not the coloured stickers on the pieces.

Like the sliding puzzle, it’s impossible to move pieces around the cube without affecting other pieces, and any scramble done from a solved state will be solvable. Also like the sliding puzzle, if the cube is scrambled by popping out pieces and reinserting them in a random order, or by rearranging the stickers, there’s a good chance it won’t be solvable and we’ll always end up with some pieces flipped the wrong way around (since every move affects other pieces, flipping a piece the right way will flip another piece the wrong way). On a 3x3x3 cube, only one in twelve scrambles done this way are solvable.

Since the cube is rule-bound and its characteristics can be understood, it’s possible to develop systematic methods for solving the cube. Indeed, advanced cube solving methods like CFOP, Roux, and Petrus break the solution down into phases, and rely on a combination of intuitive solving (figuring out the solution on your own) and algorithmic solving (memorizing a series of moves which efficiently solve recognizable patterns).

Understanding the cube also allows us to determine exactly how many unique scrambles are possible. In 1981, the original Rubik’s cube was marketed as having over three billion combinations. While this is technically true, the cube has many, many more combinations than three billion! In calculating this, we need to account for both the position and orientation of each piece.

Since there are eight corners, there are 8! (8-factorial) ways to arrange them, or 8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1. Once we’ve placed our first corner, there are seven other positions remaining for the rest of the corners. Once we place the second corner, there are 6 positions remaining, and so on. All in all, there are 40,320 possible corner arrangements!

Combinations = 8! …

Each corner has three sides, and thus three ways it can be oriented. That white-orange-green corner piece could be white-up, orange-up, or green-up. Since there are 8 corners with 3 orientations each, this would be 3^8 possible orientation combinations. However, if we remember that pieces do not move independently but affect other pieces, the orientation of our final corner is going to be determined by the orientation of the other corners. Thus, we actually end up with 3^7 orientation combinations, or 2,187.

Combinations = 8! * 3^7 …

There are 12 edge pieces, so it is tempting to say there are 12! ways to arrange them. However, each move on the cube exchanges two pieces between layers. Single face moves always swap a corner-edge pair from one layer to another, but each layer can only contain 8 pieces (centers excluded), those extra two pieces have to go somewhere else. We’re always moving an even number of pieces (or, the cube always has even parity), and there is no way for us to simply swap edge pieces. Not only do the edge positions depend on the placement of edges before them, but they also depend on the placement of the corners. We end up with 12! / 2, or 239,500,800 edge arrangements.

Combinations = 8! * 3^7 * (12! / 2) …

Each of the 12 edge pieces has two possible orientations, which would be 2^12 possible orientation combinations. However, like the corner orientations, the last one depends on the orientation of the others, so we really end up with 2^11, or 2,048 combinations.

Combinations = 8! * 3^7 * (12! / 2) * 2^11

Let’s resolve this:

Combinations = 40320 * 2187 * 239500800 * 2048

Combinations = 43,252,003,274,489,856,000

That’s over 43 quintillion! Three billion fits into this number over 14 billion times! Talk about an underestimate!